Переменная PATH в Linux

Когда вы запускаете программу из терминала или скрипта, то обычно пишете только имя файла программы. Однако, ОС Linux спроектирована так, что исполняемые и связанные с ними файлы программ распределяются по различным специализированным каталогам. Например, библиотеки устанавливаются в /lib или /usr/lib, конфигурационные файлы в /etc, а исполняемые файлы в /sbin/, /usr/bin или /bin.

Таких местоположений несколько. Откуда операционная система знает где искать требуемую программу или её компонент? Всё просто — для этого используется переменная PATH. Эта переменная позволяет существенно сократить длину набираемых команд в терминале или в скрипте, освобождая от необходимости каждый раз указывать полные пути к требуемым файлам. В этой статье мы разберёмся зачем нужна переменная PATH Linux, а также как добавить к её значению имена своих пользовательских каталогов.

Переменная PATH в Linux

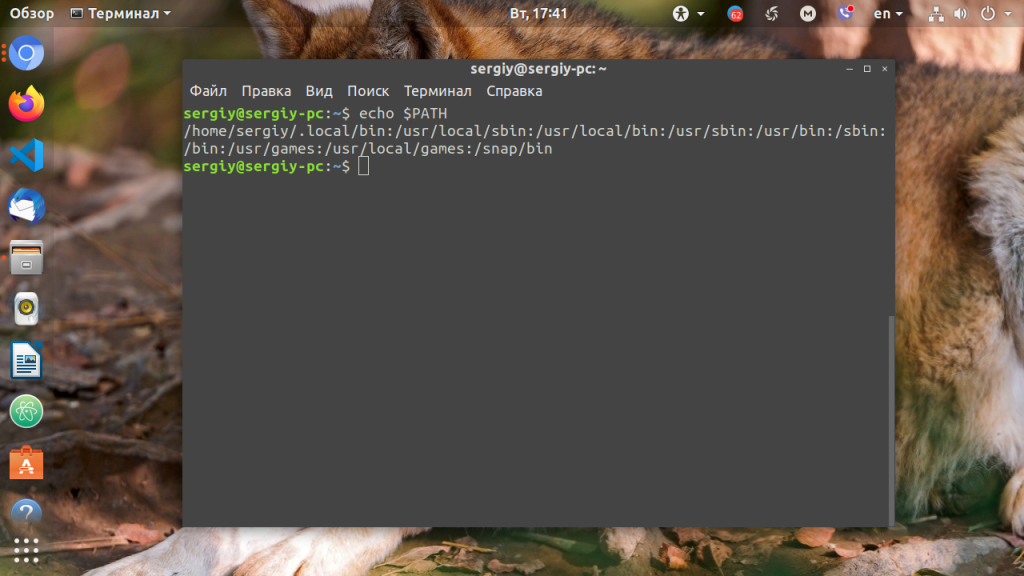

Для того, чтобы посмотреть содержимое переменной PATH в Linux, выполните в терминале команду:

На экране появится перечень папок, разделённых двоеточием. Алгоритм поиска пути к требуемой программе при её запуске довольно прост. Сначала ОС ищет исполняемый файл с заданным именем в текущей папке. Если находит, запускает на выполнение, если нет, проверяет каталоги, перечисленные в переменной PATH, в установленном там порядке. Таким образом, добавив свои папки к содержимому этой переменной, вы добавляете новые места размещения исполняемых и связанных с ними файлов.

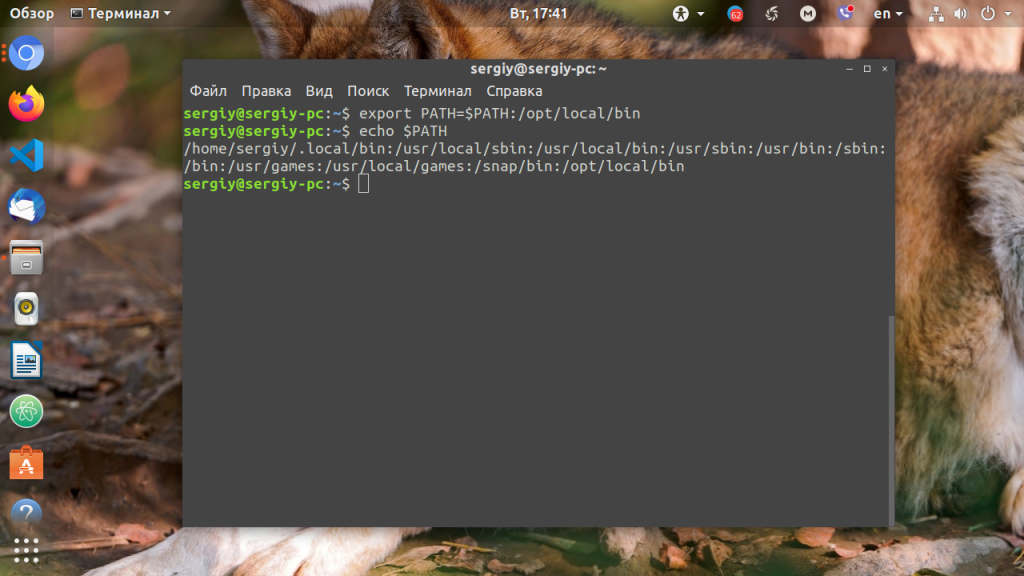

Для того, чтобы добавить новый путь к переменной PATH, можно воспользоваться командой export. Например, давайте добавим к значению переменной PATH папку/opt/local/bin. Для того, чтобы не перезаписать имеющееся значение переменной PATH новым, нужно именно добавить (дописать) это новое значение к уже имеющемуся, не забыв о разделителе-двоеточии:

Теперь мы можем убедиться, что в переменной PATH содержится также и имя этой, добавленной нами, папки:

Вы уже знаете как в Linux добавить имя требуемой папки в переменную PATH, но есть одна проблема — после перезагрузки компьютера или открытия нового сеанса терминала все изменения пропадут, ваша переменная PATH будет иметь то же значение, что и раньше. Для того, чтобы этого не произошло, нужно закрепить новое текущее значение переменной PATH в конфигурационном системном файле.

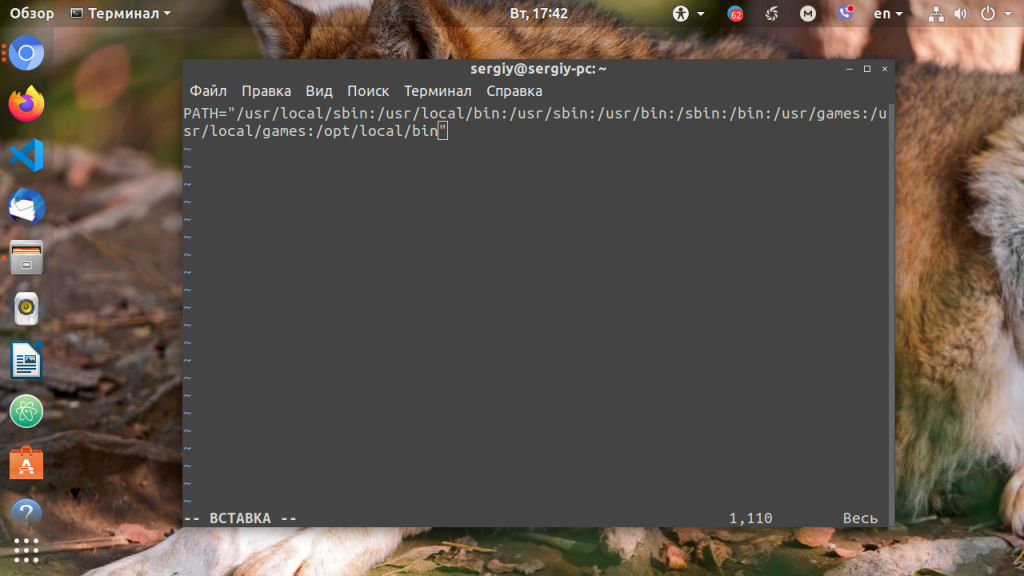

В ОС Ubuntu значение переменной PATH содержится в файле /etc/environment, в некоторых других дистрибутивах её также можно найти и в файле /etc/profile. Вы можете открыть файл /etc/environment и вручную дописать туда нужное значение:

sudo vi /etc/environment

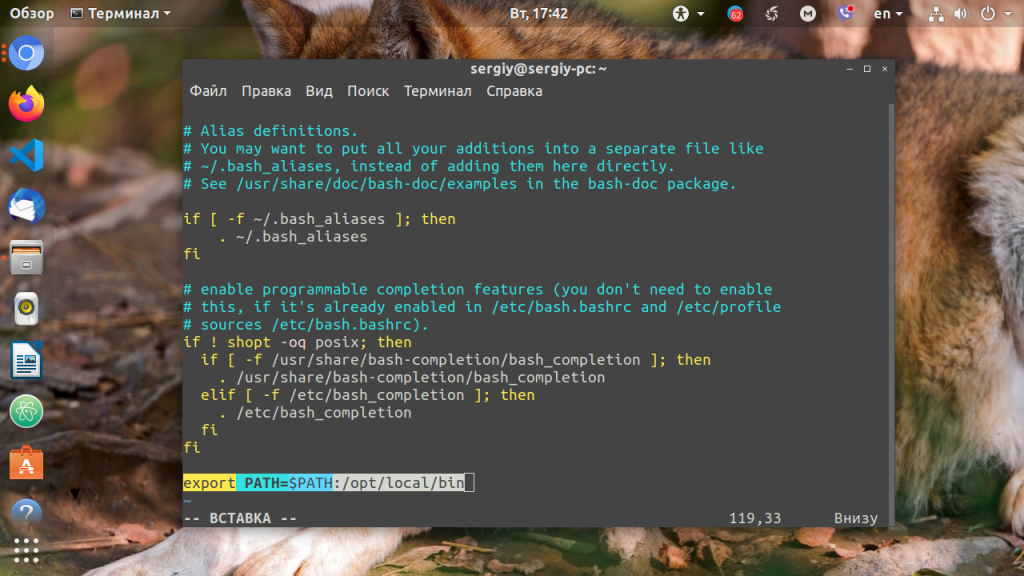

Можно поступить и иначе. Содержимое файла .bashrc выполняется при каждом запуске оболочки Bash. Если добавить в конец файла команду export, то для каждой загружаемой оболочки будет автоматически выполняться добавление имени требуемой папки в переменную PATH, но только для текущего пользователя:

Выводы

В этой статье мы рассмотрели вопрос о том, зачем нужна переменная окружения PATH в Linux и как добавлять к её значению новые пути поиска исполняемых и связанных с ними файлов. Как видите, всё делается достаточно просто. Таким образом вы можете добавить столько папок для поиска и хранения исполняемых файлов, сколько вам требуется.

How to permanently set $PATH on Linux/Unix? [closed]

Want to improve this question? Update the question so it’s on-topic for Stack Overflow.

I’m trying to add a directory to my path so it will always be in my Linux path. I’ve tried:

This works, however each time I exit the terminal and start a new terminal instance, this path is lost, and I need to run the export command again.

How can I do it so this will be set permanently?

24 Answers 24

There are multiple ways to do it. The actual solution depends on the purpose.

The variable values are usually stored in either a list of assignments or a shell script that is run at the start of the system or user session. In case of the shell script you must use a specific shell syntax and export or set commands.

System wide

- /etc/environment List of unique assignments, allows references. Perfect for adding system-wide directories like /usr/local/something/bin to PATH variable or defining JAVA_HOME . Used by PAM and SystemD.

- /etc/environment.d/*.conf List of unique assignments, allows references. Perfect for adding system-wide directories like /usr/local/something/bin to PATH variable or defining JAVA_HOME . The configuration can be split into multiple files, usually one per each tool (Java, Go, NodeJS). Used by SystemD that by design do not pass those values to user login shells.

- /etc/xprofile Shell script executed while starting X Window System session. This is run for every user that logs into X Window System. It is a good choice for PATH entries that are valid for every user like /usr/local/something/bin . The file is included by other script so use POSIX shell syntax not the syntax of your user shell.

- /etc/profile and /etc/profile.d/* Shell script. This is a good choice for shell-only systems. Those files are read only by shells in login mode.

- /etc/ . rc . Shell script. This is a poor choice because it is single shell specific. Used in non-login mode.

User session

/.pam_environment . List of unique assignments, no references allowed. Loaded by PAM at the start of every user session irrelevant if it is an X Window System session or shell. You cannot reference other variables including HOME or PATH so it has limited use. Used by PAM.

/.xprofile Shell script. This is executed when the user logs into X Window System system. The variables defined here are visible to every X application. Perfect choice for extending PATH with values such as

/go/bin or defining user specific GOPATH or NPM_HOME . The file is included by other script so use POSIX shell syntax not the syntax of your user shell. Your graphical text editor or IDE started by shortcut will see those values.

/. _login Shell script. It will be visible only for programs started from terminal or terminal emulator. It is a good choice for shell-only systems. Used by shells in login mode.

/. rc . Shell script. This is a poor choice because it is single shell specific. Used by shells in non-login mode.

Notes

Gnome on Wayland starts user login shell to get the environment. It effectively uses login shell configurations

How to set your $PATH variable in Linux

Telling your Linux shell where to look for executable files is easy, and something everyone should be able to do.

Subscribe now

Get the highlights in your inbox every week.

Being able to edit your $PATH is an important skill for any beginning POSIX user, whether you use Linux, BSD, or macOS.

When you type a command into the command prompt in Linux, or in other Linux-like operating systems, all you’re doing is telling it to run a program. Even simple commands, like ls, mkdir, rm, and others are just small programs that usually live inside a directory on your computer called /usr/bin. There are other places on your system that commonly hold executable programs as well; some common ones include /usr/local/bin, /usr/local/sbin, and /usr/sbin. Which programs live where, and why, is beyond the scope of this article, but know that an executable program can live practically anywhere on your computer: it doesn’t have to be limited to one of these directories.

When you type a command into your Linux shell, it doesn’t look in every directory to see if there’s a program by that name. It only looks to the ones you specify. How does it know to look in the directories mentioned above? It’s simple: They are a part of an environment variable, called $PATH, which your shell checks in order to know where to look.

View your PATH

Sometimes, you may wish to install programs into other locations on your computer, but be able to execute them easily without specifying their exact location. You can do this easily by adding a directory to your $PATH. To see what’s in your $PATH right now, type this into a terminal:

You’ll probably see the directories mentioned above, as well as perhaps some others, and they are all separated by colons. Now let’s add another directory to the list.

Set your PATH

Let’s say you wrote a little shell script called hello.sh and have it located in a directory called /place/with/the/file. This script provides some useful function to all of the files in your current directory, that you’d like to be able to execute no matter what directory you’re in.

Simply add /place/with/the/file to the $PATH variable with the following command:

You should now be able to execute the script anywhere on your system by just typing in its name, without having to include the full path as you type it.

Set your PATH permanently

But what happens if you restart your computer or create a new terminal instance? Your addition to the path is gone! This is by design. The variable $PATH is set by your shell every time it launches, but you can set it so that it always includes your new path with every new shell you open. The exact way to do this depends on which shell you’re running.

Not sure which shell you’re running? If you’re using pretty much any common Linux distribution, and haven’t changed the defaults, chances are you’re running Bash. But you can confirm this with a simple command:

That’s the «echo» command followed by a dollar sign ($) and a zero. $0 represents the zeroth segment of a command (in the command echo $0, the word «echo» therefore maps to $1), or in other words, the thing running your command. Usually this is the Bash shell, although there are others, including Dash, Zsh, Tcsh, Ksh, and Fish.

For Bash, you simply need to add the line from above, export PATH=$PATH:/place/with/the/file, to the appropriate file that will be read when your shell launches. There are a few different places where you could conceivably set the variable name: potentially in a file called

/.profile. The difference between these files is (primarily) when they get read by the shell. If you’re not sure where to put it,

/.bashrc is a good choice.

For other shells, you’ll want to find the appropriate place to set a configuration at start time; ksh configuration is typically found in

/.zshrc. Check your shell’s documentation to find what file it uses.

This is a simple answer, and there are more quirks and details worth learning. Like most everything in Linux, there is more than one way to do things, and you may find other answers which better meet the needs of your situation or the peculiarities of your Linux distribution. Happy hacking, and good luck, wherever your $PATH may take you.

This article was originally published in June 2017 and has been updated with additional information by the editor.